Changing Polar Ice

Uncovering A Mysterious World Beneath Greenland’s Ice

Beneath the barren whiteness of Greenland, a mysterious world has popped into view. Using ice-penetrating radar, scientists from Lamont’s Polar Geophysics Group have discovered ragged blocks of ice as tall as city skyscrapers and as wide as the island of Manhattan at the very bottom of the ice sheet. These structures apparently formed as water beneath the ice refroze and warped the surrounding ice upwards.

The newly revealed forms may help scientists understand more about how ice sheets behave and how they will respond to a warming climate. “We see more of these features where the ice sheet starts to go fast,” said geophysicist Robin Bell. “We think the refreezing process uplifts, distorts and warms the ice above, making it softer and easier to flow.”

The structures cover about a tenth of northern Greenland, the researchers estimate, becoming larger and more common as the ice sheet narrows into ice streams, or glaciers, headed for the sea. As meltwater at the bottom refreezes over hundreds to thousands of years, the researchers believe it radiates heat into the surrounding ice sheet, making the ice softer and able to flow more easily and at greater speed.

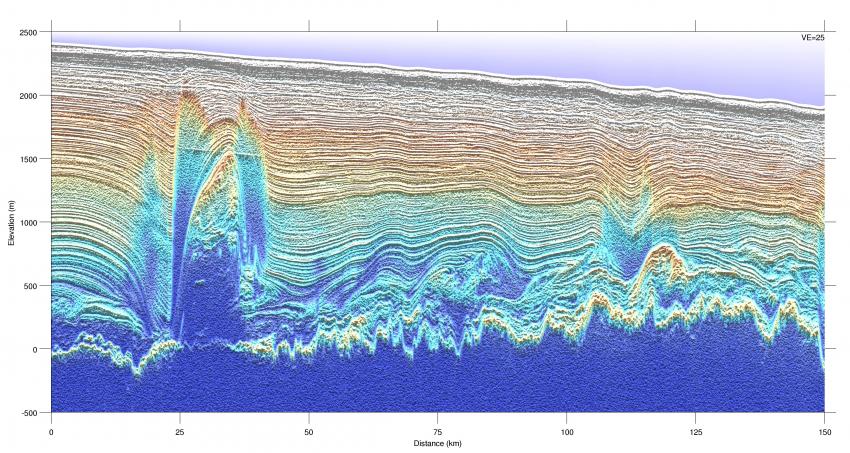

Melting and refreezing at the bottom of ice sheets warps the layer-cake structure above, as seen in this radar image from Greenland. (Mike Wolovick)

Since the 1970s, and as recently as 1998, researchers flying over the region mistook radar images of these structures for hills. Newer instruments flown during NASA’s IceBridge campaign to map ice loss at both poles found the hills to be made of ice instead of rock. Bell, who had discovered similar ice features at the base of the East Antarctic ice sheet, recognized them immediately.

While mapping Antarctica’s ice-covered Gamburtsev Mountains in 2008 and 2009, Bell and colleagues discovered extensive melting and refreezing along ridges and steep valley walls of the range. Though researchers had long known that pressure and friction can melt the bottom of ice sheets, no one knew that refreezing water could deform the layer-cake structure above. In a 2011 study in Science, Bell and colleagues proposed that ice sheets can grow from the bottom up, not just from the top-down accumulation of falling snow.

A study published by Bell and colleagues in early 2014 builds on the findings from Antarctica by linking the bottom features to faster ice sheet flow. The researchers looked at Petermann Glacier in the north of Greenland, which made headlines in 2010 when a 100-square mile chunk of ice slipped into the sea. They discovered that Petermann Glacier is sweeping a dozen large features with it toward the coast as it funnels off the ice sheet; one feature sits where satellite data have shown part of the glacier racing twice as fast as nearby ice. The researchers suggest that the refreezing process is influencing the glacier’s advance hundreds of miles from where Petermann floats onto the sea. Greenland’s glaciers appear to be moving more rapidly toward the sea as climate warms, but it remains unclear how the refreezing process will influence this trend, the researchers said.

They expected to find bottom features in the ice sheet’s interior, as they did in Antarctica, but did not expect to see features at the edges, where lakes form and rivers flow over the surface, they said. Water from those lakes and rivers appears to fall through crevasses and other holes in the ice to reach the base of the ice sheet, where some of it apparently refreezes. Their discovery indicates that refreezing and deformation at the base of the ice sheet may be far more widespread than previously thought. Bell and her colleagues believe that similar features may come to light as other parts of Greenland and Antarctica are studied in greater detail.

Flying over northern Greenland during the 2011 Ice Bridge season, Kirsty Tinto, a geophysicist at Lamont, sat up straight when the radar images began to reveal a deformed layer-cake structure. “When you’re flying over this flat, white landscape people almost fall asleep it’s so boring—layer cake, layer cake, layer cake,” said Tinto. “But then suddenly these things appear on the screen. It’s very exciting. You get a sense of these invisible processes happening underneath.”