Lamont Scientists on the Map

Since 1949, Observatory scientists have mapped the planet to gain insight into its history and evolution. In honor of these researchers’ accomplishments, many natural features bear their names, from faults on the seafloor to icy islands off Antarctica.

“Our Observatory is rooted in the notion that our planet is complicated, and that to understand all the linkages behind the phenomena we study — from earthquakes to sea-level rises, to storms and droughts — our observations must be global,” said Sean Solomon, Lamont’s director.

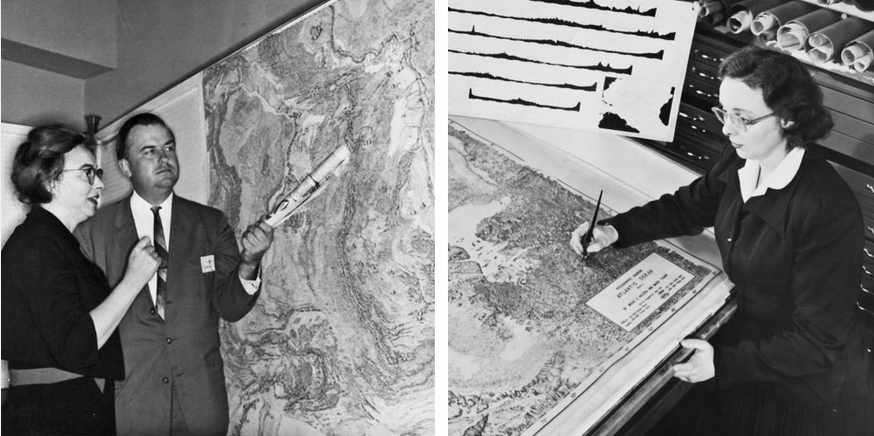

Left: Cartographer Marie Tharp and geophysicist Bruce Heezen. Right: Marie Tharp translated soundings collected at sea into the world’s first map of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The Heezen and Tharp Fracture Zones, a pair of fracture zones located in the South Pacific Ocean, are named for the late Heezen and Tharp, who together produced the first comprehensive map of the global seafloor in 1977.

The geographic distribution of the features named for Lamont scientists is vast. It ranges from the largest seamount on the Arctic Ocean’s Gakkel Ridge, named for pioneering geophysicist Marcus Langseth, to the South Pacific’s Heezen and Tharp Fracture Zones, named for the late geophysicist Bruce Heezen and cartographer Marie Tharp, who together produced the first comprehensive map of the global seafloor in 1977.

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names decides what names go on natural features on official government maps. There are naming authorities in other countries, too, but for the most part their names coincide with U.S. designations. In the continental United States, natural-feature names are restricted to people who have been dead at least five years. But in Antarctica and on the vast seafloor, the rules are a bit looser. Thus, many features there bear the names of living scientists.

Explore our new interactive feature to learn about these locations and the Lamont scientists for which they’re named.